In the latest report, “Universities Open to the World: How to put the bounce back in Global Britain”, prepared by the former universities minister, Jo Johnson recommends the UK government must consider increasing the post-study work visa to 4 years for international students amongst several other reforms.

The objectives set by the UK Government for the sector in May 2019 put us on a

trajectory that would see our market share halve by 2030 and see the UK fall down

the global rankings of destination countries. If the UK is to protect one of the few industries in which it still leads the world, it must take a number of steps to be first out of the blocks.

These include the transformation of the British Council into a body focused on

promotion of study in the UK and a strategic push to rebalance student flows by

doubling those from India.

The report suggests that the record year, ending March 2020, has seen an astounding 136% increase in Tier 4 visa approvals to Indian students, totalling 49,844.39 This achievement is thanks in part to the September 2019 announcement to introduce the Graduate Immigration Route: in the two quarters following the announcement (2019 Q4 & 2020 Q1), the Home Office received 25,159 Tier 4 visa applications from Indians, compared with 6,098 in the same period the previous year – an increase of 313%.

In the report published by the Policy Institute at King’s College London and the Harvard Kennedy School, Jo Johnson argues that “on top of the financial value that international students bring to the British higher education system and to local economies from Chichester to Aberdeen each year, the friendships they make turn into trade links, cultural bonds and diplomatic ties long after they have returned home”.

He highlights that international students are contributing to the UK’s leading research, knowledge transfer and innovation systems. As well as quoting a study in 2019, which estimated that one cohort of international graduates contributed over £3bn in tax revenues over 10 years by remaining in the UK labour market, the former universities minister insisted that attracting these future business leaders brings tangible value to the British government.

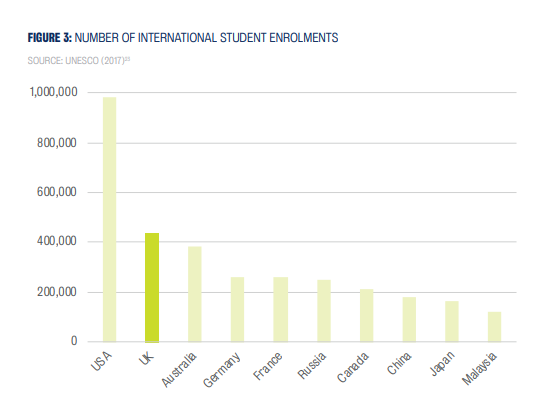

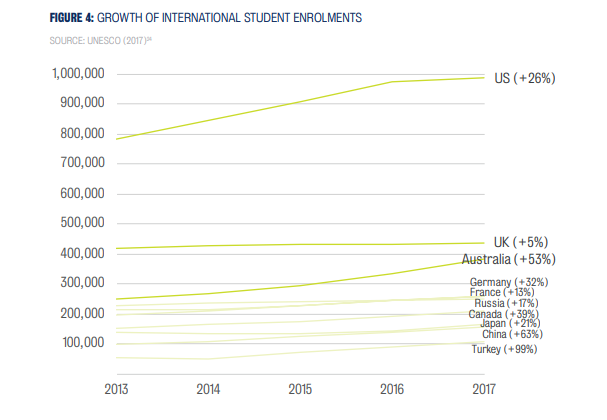

For many years, the top three destinations for international students have been the United States, the United Kingdom and Australia.

However, the UK international student numbers have in recent years been flat, for example, rising by just 0.3% in 2016 and only 0.9% in 2017. Mr Johnson says that “for much of the last decade, the UK Government has run contradictory policies aimed both at increasing education exports, while at the same time managing down international student numbers in a misguided attempt to reduce overall net migration to below 100,000”.

This confusion and ambivalence has created a volatile and unstable policy environment which helps explain why the UK – a perennial world leader in education – has gradually seen its share of the international education market slip over the past ten years he wrote in the report.

He says that “if we really care about our post-Brexit future as a trading nation, about deregulation and unleashing enterprise, we would be cutting back the time-consuming and offputting red tape affecting overseas students and instead go full throttle to achieve even more ambitious education export objectives”.

RECOMMENDATIONS FOR THE UK GOVERNMENT

Jo Johnson outlines the following recommendations for the UK government to help universities recover the damages of COVID and BREXIT:

- Set a clear ambition to retain global leadership in international education

Recommit to existing 2030 exports targets and create an additional goal for the UK to be the number one study destination worldwide after the US. - Send a clear signal that Global Britain is open and welcome, with a best-in-class student visa offer

The Government should turbocharge the competitiveness of the UK visa offer, with the doubling of post-study work visas (Graduate Immigration Route) from 2 to 4 years. - Double student numbers from India by 2024

The UK should capitalise on the post-study work visa change and seek to rebalance the mix of international students coming to the UK. It should launch a new marketing drive in India and include India, alongside China, in the low-risk country category. - Re-focus the British Council on education promotion

The British Council should be re-focused on its education promotion activity. It should establish and operate a world-class global student mobility network to replace UK participation in Erasmus; create and manage a worldwide StudyUK alumni network, and negotiate reciprocal recognition agreements with governments which don’t currently recognise degrees with significant elements of online learning. - End the hostile bureaucracy

The Home Office needs to step back, increase flexibility on English proficiency testing and Tier 4 visa issuance and hold universities to account for any non-compliance. - Prepare continuity arrangements in light of Covid-19

HMG should mitigate the effect of international travel restrictions for international students. - Put liberalisation of trade in education at the heart of FTAs

Make education exports central to the UK’s post-Brexit trade strategy, so that the UK government prioritises liberalisation of trade and cooperation in research and education in each of its prospective FTAs. - Increase transparency in progress towards the targets

Require the International Education Champion to report progress to Parliament annually.

It is to be noted that Mr Johnson is the second former universities minister to recommend 4-years work visa besides Chris Skidmore who has vocalised the need for a longer post-study work visa along with a route to citizenship for international students.

For years, however, they have had their hands tied, unable fully to unleash their potential, tied down by bureaucracy, obsessions with poorly-crafted immigration

targets and pettifogging rules. The moment has come to ensure that the UK’s great universities can play their full part in this next chapter of Britain’s engagement with

the world beyond its shores. Implementing the recommendations would not just be transformational for universities and the UK’s knowledge economy, at a time when they need a boost post-Brexit and post-COVID 19, but also give a much-needed sense of meaning and purpose to the idea of Global Britain. Seize the moment. The time for action has come. – Jo Johnson, President’s Professorial Fellow at King’s and Senior Fellow at the Harvard Kennedy School

To download the report: Universities open to the world: how to put the bounce back in Global Britain by Jo Johnson.